Search engines have evolved alongside the internet itself. This stems from early pre-web networks and human-curated directories, through to the rise of web portals and Google’s algorithmic dominance, and all to way through to mobile-first search, voice assistants, machine learning and today’s generative AI–driven experiences.

This article traces the history of search through a series of distinct eras, highlighting the technologies, companies and ideas that shaped how people find information online. It also includes a timeline of key search engine launches to show how each phase built on the last, leading to the AI-led search landscape we see today.

The Pre Search Engine Era

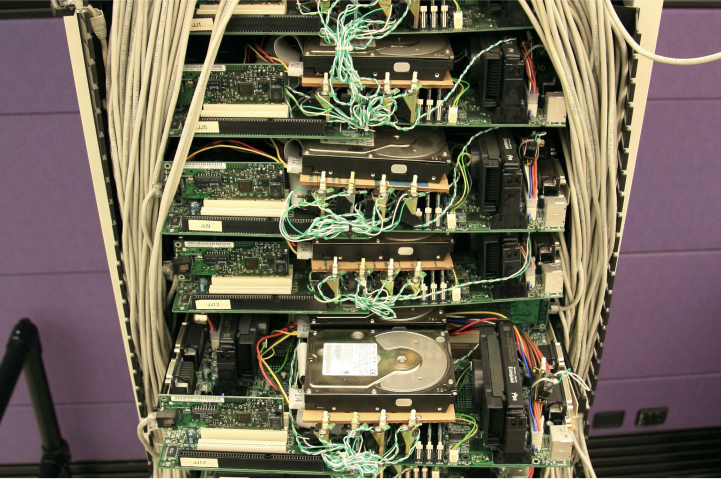

The internet existed as a concept for many years before the first search engine and even the first web page came into fruition. It was initially a US military project at DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and was used primarily as a way of sharing academic and scientific knowledge. In 1974, TCP/IP, the technology commonly known as the “internet protocol suite”, was invented by engineering duo of Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf, and laid the foundations to the frameworks of the organisation of information that the internet as we know it runs on today.

Yet the man typically associated with bringing the internet into fruition was English scientist, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, who invented the World Wide Web in 1989 while working at CERN in Switzerland. It used a technology called Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) that transmitted data over TCP/IP, which is why all URLs start with “HTTP” to this day. To make HTTP easier to interface with, Berners-Lee built the world’s first web server and web browser to navigate it in 1990. He also invented HTML (based on CERN’s SGML markup) for formatting text-based content, distributing the technology outside of CERN in 1991. Berners-Lee declared that the technology must remain freely available, with no patents or royalty-fees, to be accessible to everyone. Usenet newsgroups were how internet users communicated, a decade before the web was invented. Even after the broad adoption of Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s technology, web pages were often shared and linked to within special-interest newsgroups. Some users began creating web pages that collated the URLs shared in newsgroups, into catalogues or directories. Rather than having to download every message in a newsgroup and searching for information or URLs within them, users could now visit a directory/portal and navigate through the categories to find the relevant web pages: thus forming the genesis of what we now know as the modern search engine.

The Open Directory Project: Things Begin Taking Shape

In the late 1990s, the web still looked more like a library than a search box. One of the best-known attempts to organise it was DMOZ (the Open Directory Project), created in 1998 by two engineers at Sun Microsystems. It became a default starting point for many users because it combined human-edited categories with a search function that made browsing faster than trawling through newsgroups and link lists. DMOZ grew quickly from roughly 100,000 URLs when it was acquired by Netscape in 1998, to over a million listings a year later, eventually peaking at over five million before closing in 2017. But its credibility was gradually undermined as ownership shifted (notably when AOL acquired Netscape) and the project’s “free and open” ethos collided with commercial reality. Volunteer editors felt like unpaid labour for a corporate parent, while editorial control and impartiality were questioned as major publishers gained editing rights and accusations surfaced that some editors were selling inclusion, especially once people believed a DMOZ listing could influence search rankings. After several failed attempts to revive it, AOL ultimately took DMOZ offline. A community-led successor based on the original data still exists at Curlie.org.

Enter Archie, the First Ever Search Engine? Not Quite…

While directories like DMOZ were trying to curate the web by hand, early “search” was evolving along a different path. It’s worth clarifying a common myth. Archie, built in 1987 at McGill University, is often cited as the first search engine, but it wasn’t a web search engine. Archie indexed file names on FTP servers, helping users find downloadable files across the internet before the modern web had taken shape. Other early protocols followed similar patterns: Gopher (and search tools like Veronica and Jughead) were designed to help users navigate structured menus and filesystems, not crawl and rank web pages as we think of search today.

As the World Wide Web emerged, the first steps toward web search were still deeply connected to the directory mindset. W3Catalog (originally called Jughead) launched in September 1993 and largely made existing curated lists of web pages searchable in a standard format; closer to a searchable directory than a crawler-driven engine. The real breakthrough came with Aliweb (Archie Like Indexing for the Web), launched in November 1993, widely considered the first true web search engine. But even Aliweb reflected the era’s limitations: rather than crawling the web at scale, it relied on webmaster submissions, with site owners providing keywords and descriptions themselves.That tension defined the early web: directories promised order through human curation, while early search tools promised speed and discoverability, but lacked the automation and scale that would later make crawler-based search dominant. The next wave of engines would solve that problem by indexing the content of pages automatically, setting the stage for search to overtake directories for good.

The True Dawn of Search Engines Begins as Money Gets Involved

The first search engine to be widely used was WebCrawler, which was also the first to fully index the content on web pages. In a similar way to how search engines operate to fetch and retrieve information today, this made every word and phrase searchable. It was developed at the University of Washington and launched in 1994, the same year as Lycos, which came from Carnegie Mellon University. Both WebCrawler and Lycos became commercial ventures, with WebCrawler supported by two primary investors, one being Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

Lycos heavily invested in their brand, with TV ads featuring their iconic black labrador dog, as well as hiring a vast team of volunteer and paid editors for their web directory.

Two years after Aliweb, search engines became mainstream and big business. Excite and AltaVista both launched in 1995, along with the less well-known MetaCrawler, Magellan and Daum. But the most significant success was Yahoo, founded by Jerry Yang and David Filo.

“Yahoo!” started as a traditional web directory in 1994 by these two Stanford University graduates, though launched as a search engine in 1995. To the annoyance of their lesser-known rivals, Yahoo didn’t build any significant new technology. They bought and borrowed third-party tech, until the acquisition of Inktomi (a search engine for hire) in 2002. The success of Yahoo was all about packaging, with a fun brand and a user-friendly interface.

Internet-connected computers started to become widely accessible in schools, libraries and homes across the globe. A new generation began using websites more than books, and search engines more than web directories. Yahoo, AltaVista and Lycos dominated, with significant investment propping up the loss-making sites.

Other Players Enter the Scene and the Algorithmic Era Begins

By the mid-1990s, search was no longer just about cataloguing the web, it was about relevance. As the number of pages exploded, early engines like the aforementioned Yahoo as well as AltaVista and Excite struggled with spam, keyword stuffing and increasingly noisy results. This created the conditions for a fundamental shift: ranking pages not by what they claimed to be about, but by how the rest of the web referenced them.

Robin Li and RankDex: the Algorithm that Changed Search

One of the most important, and often overlooked, figures in this shift is Robin Li Yanhong (李彦宏). While largely unknown in the West, Li, one of the richest people in China, was and remains a foundational figure in modern search. After studying Information Management at Peking University and earning a doctorate in Computer Science at the University of Buffalo, Li worked at a New Jersey-based division of Dow Jones, where he helped build software for the online edition of The Wall Street Journal.

In 1996, Li created and patented RankDex, a system that ranked web pages using link analysis, treating links from other pages as signals of importance. This idea marked a decisive break from keyword-based ranking and predates Google’s PageRank by two years. RankDex was later cited in Larry Page’s original PageRank patent, and its core principle underpins every major search engine algorithm today. Without it, search engines may still be relying primarily on keywords rather than citations and authority.

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, Li co-founded Baidu, now China’s dominant search engine. Just as PageRank became the soul of Google, RankDex became the soul of Baidu, cementing Li’s role as a father of algorithmic search.

At the same time, another challenger was attempting to rethink search from a different angle, not through links, but through language.

Ask Jeeves: Human-Led Search Before Its Time

Launched in 1997, Ask Jeeves set out to solve a problem that frustrated non-technical users: having to “think in keywords” to get useful results. Rather than treating every word in a query as equally important, Ask Jeeves attempted to identify intent, extracting meaning from full questions like “How do I fix my computer?” rather than reducing them to awkward keyword strings.

This made Ask Jeeves hugely popular with mainstream users who were new to the web and unfamiliar with how search engines worked. In many ways, it foreshadowed today’s conversational and AI-driven search experiences.

However, Ask Jeeves struggled to scale. After being acquired by IAC in 2005 and rebranding to Ask.com in 2006, the company gradually deprioritised search technology. Its acquired engine, Teoma, failed to keep pace with the rapidly expanding web, while aggressive advertising crowded out organic results. At a time when Google’s interface was clean, fast and relatively ad-free, Ask’s results pages were often overwhelmed by display ads, particularly for commercial and technical queries.By 2010, Ask had effectively exited the search technology race, laying off its search team and outsourcing results. Ironically, a year later its CEO noted the platform still served over 100 million users per month. Had Ask continued investing in intent-based search, it might have been well positioned for the era of voice assistants and conversational queries that followed, and possibly even into the era of AI search that we are entering into now.

A Giant Enters the Fray

Against this backdrop of innovation, missed opportunities and growing frustration with spam, a relatively late entrant appeared, one that would ultimately dominate the entire landscape.

Originally called Backrub, a reference to its link-based ranking system, Google was founded by Larry Page and Sergey Brin while they were PhD students at Stanford University. The name was a play on “googol”, (ten to the power of hundred), signalling vast ambition from the outset. Before the company was even incorporated, it received a $100,000 seed cheque from Sun Microsystems co-founder Andy Bechtolsheim, followed by a $1 million seed round that included Jeff Bezos, then best known for running a fast-growing online bookstore called Amazon.

Google launched in 1998, building on ideas pioneered by others such as link analysis, but executing them with unprecedented scale and discipline. As rivals struggled with spam, cluttered interfaces and relevance issues, Google’s results felt cleaner, faster and more trustworthy. What followed was not just another competitor entering the market, but the beginning of a new era, one in which algorithmic relevance, not human curation or keyword tricks, would define search.

Early SEO Tactics and the Evolution of Google’s Algorithm

SEO started as a hobby by inquisitive webmasters who wondered how search engines ranked the order of web pages in their results. Older search engines heavily relied on trusting the “keyword” meta tag on a web page, to tell it which keyword searches to list the page for. This required a level of trust in webmasters, that they would only enter relevant keywords. Newer search engines used the content of a web page to determine its importance, often counting the number of times a keyword appeared on the page. Both of these were exploited, first for fun and then for profit. Websites would list every conceivable keyword in their meta tags and content, repeating the same keywords multiple times. These ugly lists would often be hidden at the bottom of the page or in the same colour font as the background, rendering them invisible (one form of a common spam tactic known as “cloaking”).

As mentioned earlier, Baidu founder Robin Li was one of the first to tackle this problem with RankDex, which used links from other websites as a vote of importance. Some search engines moved to this link-based citation model but counted all links as equal. Some webmasters exploited this by creating web pages with thousands of links on them, all pointing to their other websites.

Larry Page addressed this issue with his PageRank formula, which not only looked at how many backlinks a page had, but how important those linking pages were. A link from the BBC was more important than a link from a spammy hub page, as thousands of other sites would be linking to that BBC page and many of those sites would themselves have thousands of relevant links. This ripple effect was difficult to manipulate by webmasters, as every link required many levels of other links pointing at them, to help give it the authority to push a web page up the rankings.

Spam-free results became increasingly important, as the internet was used for more commercial purposes. Searches for academic papers with one or two results were replaced by tens of thousands of searches a month for [car insurance], [designer clothing] and [credit cards], each with hundreds of thousands of competing pages. Google had the magic formula for weeding out the spammy SEO keyword pages and ranking more trustworthy websites first.

Searching for Profit: The Birth of Paid Search Advertising

If the PageRank ranking formula was Google’s golden bullet, “AdWords” was the gunpowder that fired it. The computing power needed to crawl the growing web and build Page’s elaborate link graph didn’t come cheap, and all of the investors were expecting a healthy return on their investment.

Online advertising was a complex problem in 1999. Search Engines needed to place banner adverts on their search results to pay for their infrastructure, but the banner ads detracted users and slowed down their result pages. Ask Jeeves and Yahoo started to experiment with paid inclusion, where websites could pay for a higher ranking in search results or a guarantee to be listed.

GoTo.com was a minor player in the market, having bought one of the oldest search technology companies, World Wide Web Worm. Their skill was in monetising searches, creating the first ad auction system in 1998, where businesses would bid on keywords. Rather than paying for banner views, companies would pay anything up to $1 per click on their premium search result listing. The company rebranded to “Overture” in 2001 and started selling its advertising solution into MSN and Yahoo, monetising hundreds of millions of searches a day. This vastly outweighed the income from their own GoTo search engine but also gave them the capital to acquire competitor search engines, AltaVista and AllTheWeb. Other search engines were being bought for status and traffic; these purchases were purely business, increasing Overture’s ad platform coverage and keeping 100% of the revenue.

Google Gets Taken to Court

Google AdWords launched in October 2000, initially on a CPM (cost per thousand impressions) basis and transitioning to PPC (pay per click) in 2002. The PPC model was remarkably similar to Overture’s patented advertising platform. Later that year, Overture filed a lawsuit, claiming that Google had stolen their proprietary technology.

In 2003, Yahoo bought Overture for $1.63 billion. It secured the ad platform that drove most of Yahoo’s revenue, as well as increasing their market share with the portfolio of search engines that Overture had previously acquired. Then in 2004, Google settled the lawsuit with recently acquired Overture, offering Yahoo 2.7 million GOOG shares as compensation. At today’s share valuation and accounting for Google’s 2014 share split, these shares would be worth $6.9 billion.Yahoo struggled over the years to come, making poor investments, acquisitions and business priorities. Blogging, photo sharing and auction websites were acquired and then left to whither while competing websites became billion-dollar businesses. Search users left in droves, as did the partner search engines that were previously powered by Yahoo. Finally, in 2016, the company was acquired by Verizon for just $4.8 billion.

Microsoft Enters the Fray…and struggle.

Microsoft’s struggle for dominance

Nothing symbolises panic and indecisiveness better than Microsoft’s fall into the search engine world. MSN Search launched in 1998 in the wake of Google when Microsoft’s Windows operating system was used by over 90% of Americans. MSN initially used Inktomi (a search engine for hire) search results, which also powered Yahoo. They tried to stand out by blending Looksmart results and then AltaVista results into their service, with limited success.

In 2004, Microsoft finally gave search the investment that it needed, building in-house search engine technology and putting it live in 2005. MSN’s most significant success at the time was in the B2B world that Microsoft was comfortable in. They offered their technology to other search engines, internet providers and portals, gaining market share and a cut of advertising revenues.

Just as MSN Search started to pick up momentum (helped by it being the default homepage on millions of Internet Explorer browsers), Microsoft opted to rename the service “Microsoft Live” in 2006. The decision behind this is vague and perplexing, other than reinforcing the company’s “Windows” brand and making it seem modern. Just one year later, the company rebranded its search engine again, removing the “Windows” reference and calling it “Live Search”.

Bing Finally Makes Its Entrance

During a keynote at SMX Advanced in 2008, former search industry leader, Danny Sullivan asked Microsoft’s Kevin Johnson:

“Why not go back to MSN or Microsoft Search? Why not change it – or will it change?”

Johnson replied:

“There’s an opportunity for us to fix those brands. We acknowledge that we need to get that fixed. If you have suggestions, we’ll take them.”Shortly after this, in 2009, Microsoft announced that Live Search would be rebranded one last time, to Bing. The brand changes and search result quality of Microsoft became a point of ridicule over the years, but Bing became a serious contender for Google in the years that followed, and has become relevant even more in recent years with its AI integrations. It rarely gained more than a 10% market share in the US, but did compete with, and often beat, Google on blind result comparisons and user satisfaction studies. The same year that Bing launched, Microsoft signed a deal with their closest search engine rival, to power Yahoo’s search results. To this day, Yahoo is still “Powered by Bing™”.

Yandex: Russia’s Search Engine Giant (Яндекс in Russian)

Yandex (Яндекс in Russian) launched in 1997 and became the market leader in Russia in 2001. Other Russian search engines existed as well at the time, such as Aport.ru and Rambler.ru, but they later pivoted into a marketplace and media portal respectively.

Yandex’s dominance over Google in Russia stemmed from its understanding of the morphology of Russian language better, resulting in more precise search results for Russian websites. The company then released competing maps and market and shopping products, which were also better adapted to the needs of Russian users. Google didn’t seem very interested in the Russian market at first, allowing Yandex to become so dominant. As Yandex grew, search became part of a much larger ecosystem of products for the company.

However, Russian internet users have been using two search engines for several years. Thanks to the spread of Android and Chrome, Google has managed to win back a large share of search, in particular, among young and more advanced users. At one point, Google even surpassed Yandex for mobile search, but then lost its lead again, currently holding around a 25% market share in the country. Google’s Russian subsidiary also filed for bankruptcy in 2022, and amid a backdrop of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine with many Western media companies pulling out of Russia coupled with tightening media restrictions within Russia itself under Vladimir Putin, Yandex is set to dominate in Russia for years to come.

Despite this, Russia still has highly competent Machine Learning and speech recognition technology, with Yandex’s SpeechKit providing advanced speech recognition and text to speech APIs.

Baidu – The Google of China

Baidu had an impressive pedigree from the day it launched in 2000, as a Chinese focussed search engine. The company was co-founded by the aforementioned Robin Li, who we know inspired Google’s Larry Page and his PageRank patent.

The search engine’s growth was powered by ad revenue and Chinese government compliance. Baidu launched its auction-based Pay Per Click ad platform before Google but did not face the same patent infringement lawsuit from Overture that Google did. It also complied with requests to censor keywords and news sources by the Chinese government, which Google either refused or resisted. Highlighted in 2009 by a leaked internal document, Baidu had a long list of keywords, topics and websites that should return no results. It included news websites that were critical of the government, civil rights, protests, ethnic conflicts, democracy and the names of China’s leaders. This was a necessary evil, for the search engine to have any chance of succeeding within “The Great Firewall of China”.

Google began its Simplified and Traditional Chinese search engine in the same year as Baidu launched. The Chinese government intermittently blocked the .com website, so Google launched a censored version of its search engine at Google.cn. The relationship continued to be rocky though, with Google China being attacked by hackers linked to the Chinese government. It struggled to maintain a sizeable market share, with the website repeatedly blocked and Chinese users preferring native alternatives such as Baidu.

Google has since attempted to re-enter the Mainland Chinese market several times since then, with the 2018 project code named “Dragonfly” being the latest attempt to deliver a censored version of Google search in China. Despite media speculation and internal Google memo leaks, the project was canned in December 2018.

Baidu’s competition is from within China, though Bing remains a key player

Baidu has been the dominant player in China for a long time. But before Google left the Chinese market, it had almost a 50% market share. Sogou and Qihoo 360 Search (haosou.com) are also popular in China, getting most of their traffic by creating their own web browsers and other technologies such as virus software. To this day, Baidu enjoys dominance at around 65% of the total search engine market share, with Haosou and Sogou having between 5-10% respectively. Microsoft Bing, evading censorship in China, also enjoys a solid 15% search engine market share in China.

Baidu is now facing a new challenge from Toutiao Search, a predominantly mobile search portal owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance that features a heavily-personalised algorithm based on user behaviour.

A Brief History of DuckDuckGo and Privacy in Search

DuckDuckGo After Privacy

DuckDuckGo was launched in September 2008 by Gabriel Weinberg, who had recently finished his Masters at MIT and failed to launch a new social networking start-up. There were no financial backers at first, and the search results were mostly tied together from the APIs of other search engines. Why would people use it? The USP was privacy – your searches weren’t tracked or recorded like on most other search engines.

Two years prior, AOL publicly shared a data file with three months’ worth of search history, for research purposes. It included 20 million search queries from 650,000 users. While the searcher’s account details weren’t shown, they were given a random ID that allowed researchers to group searches by individual users. Some searches included PII (Personally Identifiable Information) and the identity of some users was revealed. Concerns over search privacy stopped becoming a paranoid techie issue and entered the mainstream conscience. Google itself has been the subject of a variety of privacy concerns over the years in its pertaining and storing of user data through tracking and use of cookies.

Over the next few years, DuckDuckGo started to attract a cult following of privacy-concerned users. Google and Facebook were beginning to show their cards, as collectors and sellers of personal data. In 2011, Union Square Ventures made an angel investment in DDG, “Not because we thought it would beat Google. We invested in it because there is a need for a private search engine. We did it for the Internet anarchists, people that hang out on Reddit and Hacker News”. By 2012, the search engine announced it was serving 1.5 million searches a day and made $115,000 from privacy-friendly advertising.

A year later, The Guardian and The Washington Post newspapers published an expose on an NSA operation called PRISM. PowerPoint slides leaked by Edward Snowden show how big tech companies were handing over user data and search history to US Intelligence. It stated that “98% of PRISM data is sourced from Yahoo, Google, and Microsoft”. DuckDuckGo hit 4 million searches a day that year.

There was enough demand that the Firefox and Safari browsers gave DuckDuckGo as a default search engine option in 2014. Something that Google only followed suit on in 2019.DuckDuckGo now answers 3 billion searches a month and has a market share of just under 1% globally.

The Mobile Search Era: Desktop Takes a Back Seat

People were able to search the web on their mobile device before Google was even invented, and the search giant themselves enabled their “WAP” based site for mobile users in 2000. WAP phones transitioned into “Feature Phones” such as the Blackberry, with pre-installed apps for searching and awkward navigation using a physical phone keypad or a “trackball” if you were lucky. Each device maker and telecoms company had their own deals for pre-installing a search engine on their phones, in exchange for a revenue share or contract deal.

Smartphones were the catalyst to a truly unrestricted search and browsing experience, putting a small computer in everyone’s pockets. But it also saw the collapse of a diverse phone and software market, where dozens of hardware and software manufacturers competed. The once-powerful Nokia and Motorola lost their edge and eventually got acquired by Microsoft and Google respectively. Microsoft couldn’t get a foothold in the phone market, losing out on hardware (Nokia), software (Windows Mobile) and search (Bing) revenue.

This moved the power of which search engines people used, even further into Google’s favour. Apple (iPhone) and Google (Android) were the kings of mobile. Most Android smartphones had Google Chrome pre-installed, and the search engine defaulted to Google. To make matters worse for Bing and Yahoo, Google signed a deal with Apple to make their search engine the default on iPhone’s Safari browser as well reportedly paying $9 billion a year for the privilege.

In 2015, Google announced that searches on mobile devices had outnumbered desktops for the first time, in 10 countries, including the US and Japan. This trend continues today, with mobiles and tablets becoming the primary search devices in people’s homes. Indeed in late 2025, mobile search currently accounts for a total of 60-65% of global searches.

From 2016 onwards, Google announced its “mobile-first index” which meant that websites were crawled and then subsequently indexed based on the mobile versions of their content.

Fast forward to the mid 2020s and mobile search is evolving further, this time prioritising AI-native experiences. Google AI mode as well as other Gemini-powered assistants as well as Microsoft Copilot and the ChatGPT app are reshaping how users discover information on mobile.

Within search engines themselves, rather than returning a list of links, mobile search is now more likely to surface AI-generated summaries, conversational answers and follow-up prompts, reducing friction for users but also changing how traffic flows to websites.

The Gradual Emergence of Voice Search

Voice Search, launched on Google search in 2012, was at the time framed as “the next phase of search”. The method allows users to ask their questions to a “Smart Device”, instead of typing the keywords into a web browser. This can range from a variety of devices such as smartphones, home devices such as Amazon Alex or via desktop devices directly via the means of AI assistants such as Cortana or Siri.

There was a lot of hype in the years following this, and voice search technologies have become more advanced and accessible, with more languages being made available to more people around the world. Due to this, usage has been on the rise steadily over the years with the speech recognition market projected to be valued at over $30 billion in 2030. It is estimated that up to 40% of adults use some form of voice search daily in their lives (in the US).

From a user behaviour standpoint however, voice search is unlikely to usurp traditional search methods as in most cases, voice search assistants return single answers to questions where users may want to explore a variety of answers. This is suitable for queries such as “what is the capital of France”, however for more open and subjective queries, users expect more information from their search engines.

Despite growth in usage and availability, voice search does remain somewhat of a novelty in answering closed questions such as the above, getting the weather forecast, playing games or getting the device in question to play music or the radio.

From a Microsoft standpoint, the Cortana voice assistant struggled to make a market outside of the Windows desktop app, and was largely discontinued with Microsoft removing it from its mobile apps in 2023 to focus more on Microsoft Copilot.

Amazon is the surprise winner in the smart speaker battle, with 61% market share in the US alone. This beats Google Home’s 23% market share. While Amazon did own a search engine called. A9 (run by former WebCrawler and AltaVista execs), the technology focuses on product and enterprise search and was eventually retired and redirected to Amazon.com in 2019.

Instead, Amazon Alexa web searches are powered by Bing, giving Microsoft an upper hand over Google for the first time. Sometimes it pays to be 2nd best, especially when a trillion-dollar company is an arch-rival of the top search engine.

The problem with voice search is that no matter how realistic the synthetic voices sound, nobody wants to hear a computer read the web pages of the top ten search results to them. Voice search will remain a mostly one-way conversation, used to answer simple questions, carry out tasks and sometimes complete basic transactions. They say that a picture is worth a thousand words – Alexa and Google would take roughly 10 minutes to say those words compared to the seconds needed to skim-read a web page and identify the information required.

The Great Glasses and Wearable Tech Flop

Google Glass, which launched to the public in April 2014, struggled to gain mainstream adoption. While the technology itself was innovative, its positioning proved challenging. As a wearable designed to be worn on the face, Google Glass sat at the intersection of technology and fashion, yet its early rollout focused more on technical capability than lifestyle appeal. This made it difficult to resonate with a broader consumer audience, particularly when compared with other fashion-led consumer electronics.

Early preview devices were primarily distributed within technology circles, shaping perceptions of Google Glass as a niche product rather than a desirable everyday accessory. Combined with public concerns around privacy and usability, this limited its appeal and contributed to its eventual withdrawal from the consumer market.

However, the broader wearable technology sector continues to grow, and smart glasses have not disappeared. Google Glass has since found more practical applications in enterprise and industrial settings, where it is used to support tasks such as warehouse logistics and access to contextual information in healthcare environments. At the same time, new entrants in the smart-glasses space have focused more heavily on design and consumer appeal, while major technology companies, including Amazon, continue to explore wearable and augmented-reality devices as part of their longer-term vision for ambient computing.

Despite this failure, Google have publicly declared that they are going to “try again” with smart glasses in 2026, with promises to integrate AI features such as Gemini. Watch this space…

The Machine Learning Era: Search Changes Drastically

Search engines have been using machine learning in some form for many years, with Google announcing its intention to become a “machine learning–first company” in 2016. Google AI followed in 2017, and in 2018 the company introduced the language model BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) a major step towards understanding the intent and meaning behind search queries rather than simply matching keywords.

BERT and subsequent machine learning models enabled search engines to move away from literal keyword matching and towards semantic interpretation, using context, language patterns and prior behaviour to better anticipate what a user is actually searching for. This shift accelerated the prominence of answer-focused SERP (search engine results page) features, such as featured snippets, answer boxes and People Also Ask, where search engines began surfacing concise answers directly from web content without requiring a click-through. As a result, many queries increasingly became “no-click” searches, with users finding what they needed directly on the results page.

This approach developed further with the launch of Google’s Multitask Unified Model (MUM) in 2021, framed as a significant upgrade to BERT. MUM allowed search engines to support more complex, multi-step queries by suggesting follow-up questions and guiding users through broader discovery journeys. For example, a query such as “where to visit in Japan” might surface an initial answer alongside prompts like “where to visit in Japan in autumn”, “cultural nuances to remember when visiting Japan” or “when is the best time to visit Kyoto”, refining intent over successive interactions. This was a clear shift towards keeping the user journey within search results and was a big step towards what we now know as AI search.

Along with this, search engines expanded their role beyond information retrieval into comparison and transactional experiences more broadly. Features such as flight search, hotel pricing and credit card comparisons increasingly appeared directly on the SERP, allowing users to research, compare and make decisions without visiting third-party websites. Over time, this positioned the SERP itself as a transactional layer, capable of hosting product information, imagery and pricing, and potentially even checkout experiences. In this model, search engines capture value not just from clicks, but from facilitating the entire journey.

More broadly, machine learning-driven chatbots and automated answering systems have already become commonplace in sectors such as financial services, handling factual, numerical and transactional tasks including balance checks, account management and credit decisions. Within search, these developments collectively set the stage for the next evolution: generative AI, where answer-heavy, intent-led and journey-based SERPs transition into fully conversational and AI-generated search experiences.

When it comes to search engines, financial aspects such as intelligent flight and credit card comparison services, served directly on the search results have been a feature in recent years. It’s only a matter of time before search engines take over the entire transaction process from the SERP. The user will be saved the hassle of navigating through and ordering on a third-party website. The products, images, content, shopping cart and checkout can all be served on the SERP. Search engines would get a cut of the overall transaction, instead of just a dollar for the click. Users feel safer with their money stored and managed in a “Google Wallet”.

Of course, this isn’t a process that Google or search engines has pioneered or owned outright. We’ve seen the emergence of ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity and other LLMs come to shape this new era of search, which sets the stage for the current and future stage of search: generative AI.

The Generative AI Era

Large language models (LLMs) have been around for some time, with GPT1 launching in 2018 by AI company OpenAI.

However, the current generative AI era in search began in earnest in late 2022 with the public release of ChatGPT, built on OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 large language model. Unlike earlier conversational assistants, ChatGPT demonstrated an unprecedented ability to respond coherently to complex, multi-part questions, assist with coding and debugging, generate long-form content, and reason across topics, albeit with limitations around accuracy and factual reliability.

The rapid adoption of ChatGPT brought large language models into the mainstream almost overnight and represented a clear inflection point for search. For the first time, a consumer-facing AI product showed that users were willing to ask questions conversationally and accept synthesised answers, rather than navigating a list of links.

Internally, this triggered what was widely reported as a “Code Red” moment at Google, reflecting the perceived commercial threat posed by LLM-powered interfaces to traditional search behaviour. While other models and assistants existed, including Anthropic’s Claude (as well as Grok, of X, formerly Twitter) ChatGPT was the catalyst that accelerated the industry’s shift from intent-led search to answer-led experiences.

Search Engines Respond: Gemini, AI Overviews and Copilot

Search engines moved quickly to adapt, repositioning themselves as hybrid platforms combining traditional search results with generative AI answers.

Google’s response took shape with the launch of Search Generative Experience (SGE) at their I/O in May 2023, which later rebranded as AI Overviews. Built on Google’s Gemini family of models, AI Overviews introduced AI-generated summaries at the top of certain search results, designed to synthesise information from multiple sources and allow users to explore follow-up questions directly within the SERP. This approach extended the trajectory set by BERT and MUM, shifting search further towards guided discovery and semantic understanding.

When AI Overviews began rolling out more broadly in the US in spring 2024, they attracted significant attention and criticism. Early examples highlighted issues with hallucinations, misleading answers and questionable sourcing, raising concerns among publishers, businesses and users alike. Many publishers and news based sites (such as the Reach plc in the UK) reported major concerns in traffic (and knock on advertising revenue) loss owing to AI Overviews summarising news article content taken from these sites in search results, thus negating the need for users to click through.

As of 2025, the feature remains iterative, with Google balancing accuracy, user engagement and commercial considerations as it integrates Gemini more deeply into search. Along with AI Overviews featured increasingly prominently in search results, Google went further by launching AI Mode in mid-2025 inherently as a separate, AI-focused feature within Google search as well as their Gemini offering (formerly known as Bard) AI virtual assistant feature which saw a general release in February 2024.

Many commentators opined that the latest iteration of Gemini, Gemini 3, released in November 2025, rivalled and even surpassed the capabilities offered by ChatGPT 5.

Microsoft followed a parallel path, embedding Bing Chat and later Microsoft Copilot directly into Bing search results in early 2023. Leveraging its partnership with OpenAI, Microsoft positioned Bing as an AI-enhanced alternative to Google, with conversational responses sitting alongside traditional listings.

In China, Baidu’s Ernie Bot was released to the public in August 2023, reflecting a similar shift toward generative answers within a tightly regulated domestic search ecosystem. A year later, Baidu reported a 300 million strong user base.

Across markets, the pattern is consistent: search engines are evolving into search-plus-assistant hybrids, blending retrieval, summarisation and conversation within a single interface.

Money, Valuations and Strategic Deals in the AI Search Arms Race

Underlying these product changes is an unprecedented flow of capital, infrastructure investment and strategic partnerships.

Microsoft’s multi-billion-dollar investment in OpenAI fundamentally reshaped the competitive landscape, tightly coupling Bing, Copilot and Azure to OpenAI’s models and positioning Microsoft as a central player in AI-powered search and productivity. Google, meanwhile, has committed heavily to AI research, custom silicon and large-scale infrastructure to support Gemini, reflecting a long-term bet on AI as core to its search and advertising businesses.

Newer entrants have also attracted significant funding. Perplexity AI, positioned as an “answer engine” combining LLMs with real-time web retrieval, has raised multiple rounds at multi-billion-dollar valuations, signalling investor confidence in alternative search models. At the same time, companies such as Anthropic and xAI have drawn substantial investment, alongside a broader migration of talent and capital into AI-first search and assistant platforms.

Collectively, these deals reflect a shared assumption across the industry: that search is evolving into a conversational, assistant-led layer, embedded across devices, operating systems and applications, not confined to a traditional results page.

New Entrants and Alternative Search Experiences

This shift has reopened a question that once seemed settled: will anyone overtake Google? While previous challengers, including Bing, struggled to meaningfully disrupt Google’s dominance, the rise of LLM-native products introduces new dynamics.

Platforms such as Perplexity AI prioritise direct answers and citations over ranked links, while services like Brave Search, Kagi and You.com experiment with alternative models built around privacy, subscriptions or vertical-specific search experiences. OpenAI itself is increasingly positioning ChatGPT as a search-capable assistant, blurring the boundary between chatbot and search engine.

While it remains unclear whether these players will materially shift market share, they represent credible experiments in redefining what users expect from search, particularly for informational and research-driven queries.

What This Means for Businesses and SEO Moving Forward

For businesses and publishers, generative AI has already begun to change the mechanics of search visibility. Features such as AI Overviews and conversational answers can reduce click-through rates for some traditional listings, particularly for informational queries. At the same time, being referenced or cited within AI-generated answers introduces a new form of visibility that extends beyond classic rankings.

As a result, success in search increasingly depends on producing authoritative, well-structured and up-to-date content that can be easily interpreted and trusted by AI systems. Clear, factual information, strong entity signals and solid technical SEO foundations remain critical, ensuring content is both crawlable and usable within AI-driven retrieval and summarisation pipelines.

Ultimately, large language models have changed what “search visibility” means. It is no longer defined solely by blue links and rankings on certain keywords, but by how effectively a brand or source can participate in AI-led discovery, answers and decision-making journeys within modern search experiences.

A History of Search Engines in Dates

| Search Engine | Launch Date | Description |

| Archie | 1990 | The first internet search engine. |

| Gopher | 1991 | A file search protocol used before the web. |

| Veronica | 1992 | A search engine for the Gopher protocol. |

| Jughead | 1993 | Another Gopher search engine. |

| WebCrawler | 1994 | The first full-text search engine. |

| Lycos | 1994 | Early search engine with a large index of documents. |

| Yahoo! Directory | 1994 | A human-edited directory. |

| Infoseek | 1994 | Another early web search engine. |

| AltaVista | 1995 | Notable for advanced search capabilities. |

| Excite | 1995 | Known for web portal features. |

| MetaCrawler | 1995 | A metasearch engine aggregating results. |

| Daum | 1995 | South Korean web portal with search capabilities. |

| Inktomi (HotBot) | 1996 | Powered several major search engines. |

| Ask Jeeves | 1996 | Known for natural language queries. |

| Dogpile | 1996 | Another metasearch engine. |

| Seznam.cz | 1996 | Czech search engine. |

| Rambler | 1996 | Russian search engine. |

| Northern Light | 1997 | Unique categorisation of results. |

| Yandex | 1997 | Leading search engine in Russia. |

| 1998 | Introduced a link analysis algorithm. | |

| Naver | 1999 | Major search engine in South Korea. |

| Teoma | 2000 | “Subject-Specific Popularity” algorithm. |

| Baidu | 2000 | Major search engine in China. |

| AlltheWeb | 2000 | Known for its comprehensive index. |

| Wisenut | 2001 | Acquired by LookSmart. |

| Gigablast | 2002 | An open-source search engine. |

| A9.com | 2004 | Amazon’s search engine. |

| MSN Search | 2004 | Microsoft’s early search engine, evolved into Bing. |

| Sogou | 2004 | Popular Chinese search engine. |

| Yippy | 2004 | Clustered search results. |

| Yacy | 2004 | Peer-to-peer search engine. |

| Ask.com | 2006 | Rebranded from Ask Jeeves. |

| Startpage | 2006 | Privacy-focused search engine. |

| Mahalo | 2007 | Human-powered search engine. |

| Cuil | 2008 | Large index and different search methodology. |

| DuckDuckGo | 2008 | Focuses on user privacy. |

| Ecosia | 2009 | Eco-friendly search engine. |

| Bing | 2009 | Microsoft’s search engine. |

| WolframAlpha | 2009 | Computational knowledge engine. |

| Blekko | 2010 | Spam-free search results. |

| Qwant | 2013 | Privacy-oriented European search engine. |

| Brave Search | 2021 | Privacy-focused search engine by Brave Software. |

| ChatGPT | 2022 | LLM-powered conversational interface increasingly used for search-like queries. |

| Perplexity AI | 2022 | AI-powered “answer engine” combining LLMs with web retrieval and citations. |

| Bing Copilot | 2023 | Generative AI assistant integrated directly into Bing search results. |

| Google Gemini | 2023 | Google’s LLM used to power Google AI Mode, AI Overviews and the Gemini virtual assistant itself |